| |

Papillion Times

Making

the world a better place

Paplo

grad brings hope to Tanzania

April 30, 2010

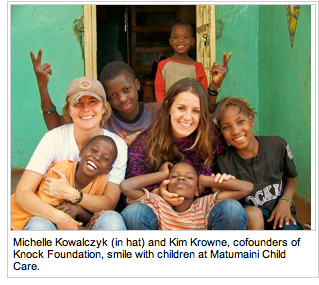

Michelle Kowalczyk looks like a typical pretty, young woman in America — a curly-haired brunette sporting a long-sleeve shirt, scarf and jeans. No one would guess that she could carry on a conversation in Swahili or that, although living stateside, her heart is really in Tanzania, Africa. Michelle Kowalczyk looks like a typical pretty, young woman in America — a curly-haired brunette sporting a long-sleeve shirt, scarf and jeans. No one would guess that she could carry on a conversation in Swahili or that, although living stateside, her heart is really in Tanzania, Africa.

Kowalczyk, a 1999 graduate of Papillion-La Vista High School, is a founder and managing director of the Knock Foundation, a small grassroots organization with a mission to “support impoverished communities throughout the world,” according to the organization’s Web site, knockfoundation.org.

Kowalczyk’s work is currently helping Rau, a village in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania, in a variety of ways.

“We have lots of different projects,” she said. “We kind of defer to their needs, (asking) ‘What do you guys want? What can we do to help you get there?’”

The path from Papillion, Neb., to Rau, Tanzania began with a trip in 2006. Kowalczyk said she always knew she wanted to take a trip to Africa. So, she did her research and found organizations that went there. After making a list, she narrowed her choices by looking at each organization’s mission statement. She finally landed on Cross Cultural Solutions, the international arm of CARE (a humanitarian organization fighting global poverty, according to its Web site), which gave her a choice between Tanzania and Ghana.

She chose Tanzania because it was “more rural.” As a nurse, she was assigned to a mother-child clinic.

During her first week, she met Kim Krowne, who had been there for three months and was preparing to return home to Northridge, Calif. During her stay, Krowne had spent a lot of time at an orphanage, the Matumaini Child Care Center, which opened in October 2006.

So Krowne had a request for Kowalczyk.

“She said, ‘Can you go and see the kids? They’re used to seeing me every day,’” Kowalczyk said. “So every day after work, I would go. It went from playing to caring for them.”

Because she cared for them, Kowalczyk cared that their living situation was harmful to their well being. Their latrines were unsanitary, they slept up to six on a “bed” (or foam mats), and they had no mosquito nets, exposing them to frequent malaria.

(In Africa, any child who has lost one parent is considered an orphan; many times the one living parent is unable to care for his or her children. All but two of the children at Matumaini are considered orphans.)

So Kowalczyk and others improved the latrines, built bunk beds and bought mosquito nets, which she said helps guard them against malaria. They do still get it, but less frequently than they used to.

During her stay, Kowalczyk continued to e-mail Krowne, updating her on the kids. Then, when it was Krowne’s turn to return to Rau and Kowalczyk came back to the States, Krowne returned the favor and continued to send updates.

While in the States, Kowalczyk began doing some fundraising for Matumaini.

“I realized … when you’re an adult, it’s really nice to get tax exemption,” Kowalczyk said. “It’s a lot easier to get donations from people if they get something back from it.”

So Kowalczyk applied for nonprofit status. She, Krowne and three others — Barry Krowne (Kim’s father), David Grossman and F. Bruce Cohen – created the Knock Foundation.

“We were already doing work when we decided to (create) Knock,” Kowalczyk said. “Once we got our status, we started getting donations. It just kind of grew into what it is today.”

It wasn’t some ambitious goal to save the world, she said.

“We just needed money to do the work we were doing.”

Knock started supporting Matumaini’s budget in January 2007. In June 2007, Knock was able to fully support the orphanage’s operating budget.

The biggest project the founders of Knock are fundraising for this year is a new building for the Matumaini Child Care Center, which will cost a total of $250,000.

Currently, the 21 children housed there are living in a three-room building.

“It’s really small. It’s not a good place for them to be able to learn or do homework. There’s nowhere to eat,” Kowalczyk said.

Once the new center is built, Matumaini will be able to house 40 children.

“We won’t increase the number of kids right away though because of funding constraints,” she said. “We will increase it once we can support an operating budget of 40 kids.”

The new building will be a community center with a girls’ dorm, boys’ dorm, some classrooms, a dining hall, and an administration block. The Knock Foundation does a lot of community outreach, teaching seminars and providing counselors, so the extra space will help them to better serve the community of Rau. Every year, Knock hosts a life skills seminar on subjects such as self-confidence, healthy relationships, gender roles and family planning. The first year, 100 people showed up. The next year, it doubled.

The vast majority of children at Matumaini go to Mrupanga Primary School across the street. Knock pays for all of the Matumaini children’s school fees. In addition, Knock also pays for the lunches of all 350 students at the school as well as a cook.

“We do lunch support for them because the kids weren’t eating lunch, and kids can’t learn without eating lunch,” Kowalczyk said. “For a lot of kids, that’s the only meal they get all day. So we thought it was really important to pay for lunch.”

With the help of a private school in Los Angeles, the textbook-student ratio has been reduced from 7-to-1 down to 2-to-1. In addition, Knock has also finished a classroom and provided desks for many of the classrooms.

Because the Matumaini Child Care Center is limited to only 20 children (although one “slipped through,” Kowalczyk said with a laugh, bringing the total to 21), that leaves more orphans without a place to stay. So Knock started the Piggery Project as a means of extra income for families that take in orphans.

Through the Piggery Project, families can apply to be part of the program, which provides them with the materials to build a banda, or hut, for the pigs, Kowalczyk said. Once their banda is approved, they receive two piglets, which are routinely checked on. Once the piglets grow and give birth, the family gets to keep two-thirds of the profit; one-third goes back into the project. So far, 50 bandas have been built and Knock recently submitted a proposal for 250 more.

Kowalczyk said being there so much has made her somewhat desensitized to the poverty, although when she watches a child die of malaria “it’s always a slap in the face.”

She said it’s heartbreaking to know that some of the children no longer have parents, and even no family at times. One little boy who lives at Matumaini, Stefani, is an orphan with no siblings, which is rare, Kowalczyk said.

“We found Stefani crying one day and he said, ‘My daddy’s dead and now I’m an orphan.’ It was like, right, of course. At the time he was 7. It was just really …” Kowalczyk paused. “To have a 7 year old deal with that is awful.”

While working on the Piggery Project, she once got to see the hut where Stefani had lived for five years of his life.

“I’m not a very emotional person as far as tears go and I was instantly in tears. It was so small; it was just sticks. No windows. There was nothing. His dad’s grave was in the back. It was such a reality.

“We’ve tried to create a family atmosphere as much as possible, but to think that they won’t ever have parents, that support,” she said. “It’s kind of heartbreaking sometimes.”

But one thing that sticks out to her is how happy the kids are.

“They don’t know any different,” she said. “They don’t know this life. I don’t know if they’d be happy (here) anyway. They’re just like kids here. They like to play and have fun.”

Knock puts a high emphasis on education, which itself is sustainable, Kowalczyk said. Through the Knock Foundation, anyone can support a child’s education through a one-time donation of the total cost of secondary school. Kowalczyk said sometimes in the past, people have generously offered to put a child through secondary school, but then get busy and forget. Then the child has to quit school because he or she no longer has a funder. To prevent that from happening, Knock asks for the total cost upfront.

The approximate cost for four years in a government school is $1,500 and for four years in a private school is $5,000. Although the private schools are considerably more expensive, Kowalczyk said the education is considerably better and worth the extra money.

“People are always wanting to volunteer, which is fantastic, but we don’t have much for people to do over there just yet. For the most part what we need, unfortunately, is money.

“We still have a whole page of things we would do if we had funding,” she said. “Funding has been holding us back since we first started.”

Knock is about $30,000 away from the $250,000 needed to build the new orphanage.

On May 26, Knock is holding a fundraiser that will be held at the Papio Bowl from 6:30 to 9 p.m. Tickets are $25 each (or $15 for students), which includes cosmic bowling, shoes, pizza and soda. Lane sponsorships are also available for $175, which includes five general admissions and a lane recognition banner. All of the proceeds will go toward the new Matumaini Child Care Center.

Donations can also be made online at knockfoundation.org.

“The positive thing that stands out the most is that people (in Tanzania) are so thankful for what they have. They don’t get jealous of other people,” Kowalczyk said. “They’re driven, but they don’t want for more. They’re always so concerned, so caring. They’re really amazing people. If has given me a perspective on life I will never, ever lose. They’ve taught me a lot for sure.”

Read Article On Papillion Times Website

Return To The Press |